Cybersec Canon Ep 6. The Cuckoo’s Egg - Chapter 17-23. The Science of Tracing

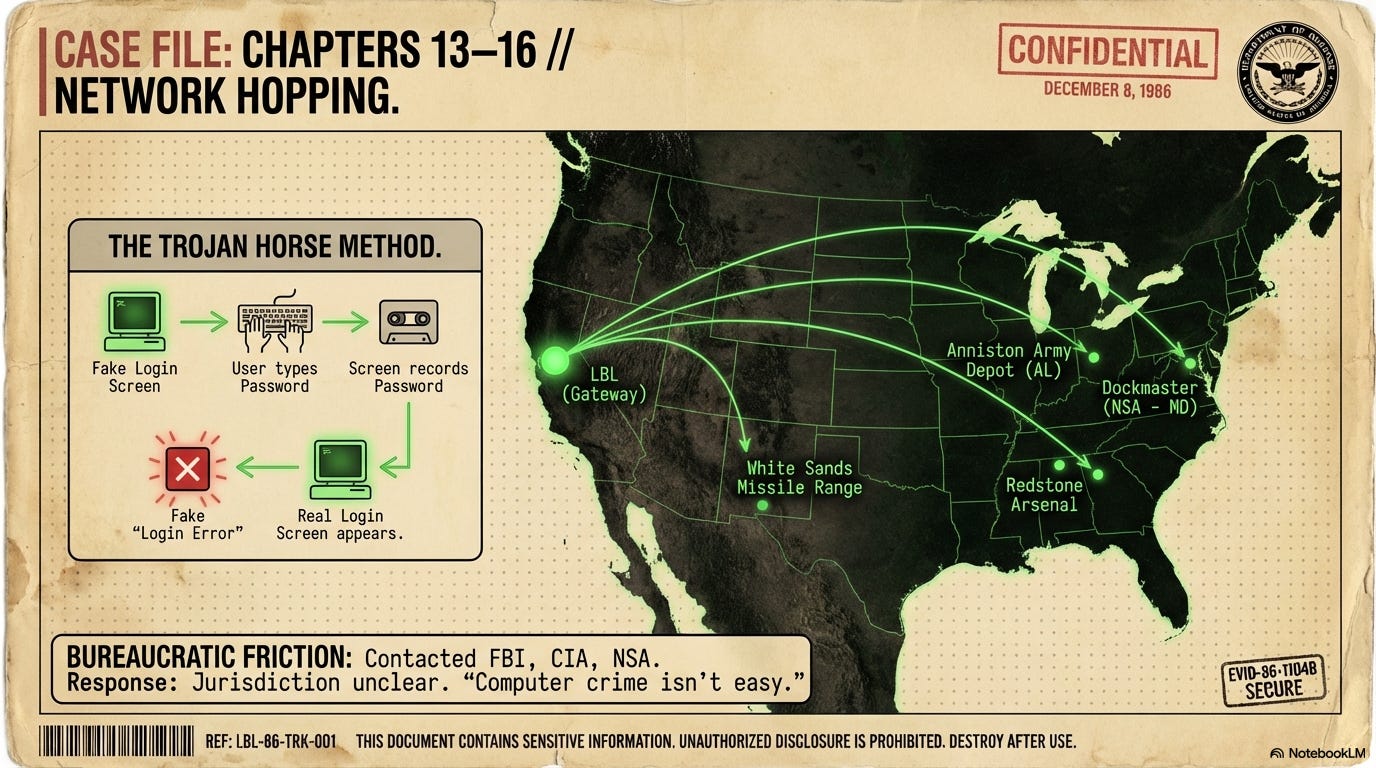

Cliff uses physics to learn that the hacking is originating from outside of the US. He faces bureaucratic barriers and is frustrated at the inability to navigate the non-scientific maze.

The echoes tell you how far the sound traveled. To find the distance to the canyon wall, just multiply the echo delay by half the speed of sound. Simple physics.

Stoll, Clifford. CUCKOO’S EGG (Chapter 17). Kindle Edition.

I’m restarting this newsletter and hoping to commit to posting something every week. For a moment, I was wondering if chronological reading of the Cybersecurity Canon made sense or not. I guess I’ll stick to this for a few more weeks and see how it works. Since it has been a while, there is a quick recap at the end of this post.

Summary

Chapter 17: Physics and Echoes

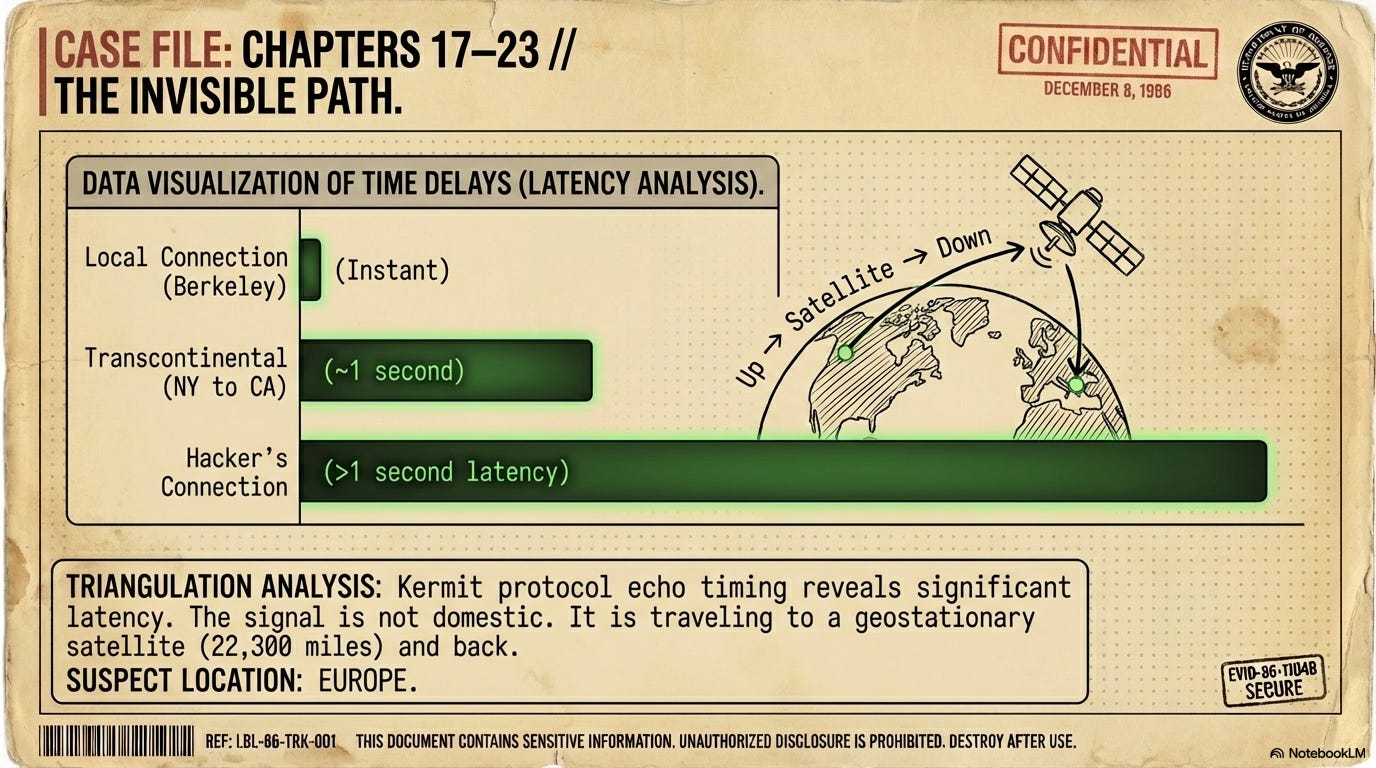

The 3-week period to catch the hacker is over. Cliff wonders if he should just plug the hole in his systems and focus on other things, especially because he didn’t hear back from the agencies that he spoke with. That would mean protecting Berkeley’s systems, but the hacker could be infiltrating other high-value targets. Also, what if there is another security hole that he is not aware of, but the hacker is? When he monitors the hacker using the Kermit file transfer program, he wonders why there is a delay in back-and-forth communications. Then it hits him that he could calculate the distance between the hacker and himself using the time taken for round-trip data transfers, like measuring distance using echo. He finds that there is over 3 seconds of round-trip delay in the hacker’s communications. This could mean that the hacker is really far away because even if the hacker were to use a satellite to communicate, you’d need twelve satellite hops to account for a three-second delay. He deduces that the hacker is using networks that move his data inside of packets, and since the packets are constantly being rerouted, assembled, and disassembled, it might account for the time delay. In the end, Cliff is still uncertain whether the hacker is 6000 miles away or somewhere nearby.

Chapter 18: Pseudonyms and Patience

The hacker’s activity becomes more frequent. Cliff connects with Dan Kolkowitz at Stanford, who is dealing with a hacker using the pseudonym “Pfloyd.” A newspaper article in the San Francisco Examiner conflates the Stanford and Berkeley hackers, leading Cliff to fear the intruder will disappear. However, the hacker returns, proving to be methodical and disciplined. Cliff notes that the hacker remembers exactly where he “laid an egg” (a back-door file) in a system three months prior, suggesting this is a professional rather than a “college joker.”

Chapter 19: The Scrabble Connection

Cliff notices the hacker changed all his passwords to “lblhack.” Through a conversation with Maggie Morley, the lab’s document specialist and a Scrabble enthusiast, Cliff learns that the hacker’s previous passwords “Jaeger,” “Hunter,” “Benson,” and “Hedges”, are linked. “Jaeger” is German for “Hunter,” and “Benson & Hedges” is a brand of cigarettes. This insight gives Cliff a humanizing detail: his target is a methodical smoker with a grasp of German!

Chapter 20: The Halloween Trap

On Halloween, when Cliff is just about to go to the party in the evening, the hacker breaks into a new, mismanaged “super-minicomputer” at the lab called the Elxsi. The hacker exploits a wide-open UUCP (Unix-to-Unix Copy) account to gain system privileges. Cliff finally makes it to the party late and dresses up as a Cardinal. Cliff realizes the hacker isn’t a “wizard” but is simply persistent and knows which “unlocked doors” to poke. To keep up with the intruder without living at the lab, Cliff buys a pocket pager and programs his monitors to alert him the moment the hacker logs in.

Chapter 21: The Bureaucratic “Bailiwick”

Cliff begins reaching out to higher-level government agencies, including the Department of Energy (DOE) and the National Security Agency (NSA/NCSC). Every agency expresses interest but claims they lack the jurisdiction or “charter” to actually help or issue a search warrant. Dejected, he walks around the LBL hallways looking up at the exposed pipes in the ceiling and realizes that he has become personally responsible for the security of the network community.

Chapter 22: The Virginia Trace

Cliff discovers via a law library computer that he doesn’t actually need a search warrant to trace a call made to his own phone, but the phone companies remain uncooperative. Cliff tells his friends Terry and Jerry over lunch about this - that the phone operators trace the call but don’t tell him the number. They look at his notes and see that Cliff had written 703 and C & P and deduce that 703 is the area code for Virginia and C & P could be Chesapeake and Potomac. Jerry asks him to try different permutations. Cliff calls the operator and gives him 6 numbers and says that he got billed for calls from them. The operator is helpful and says 5 of the 6 are not valid numbers. So he is able to narrow down to one number and finds out that it belongs to Mitre Corporation, a defense contractor located just miles from CIA headquarters.

Chapter 23: Reaching Out to Mitre and the CIA

Cliff confirms the Mitre connection by “trading” astronomical posters to a phone technician for a verbal confirmation of the trace. He contacts Mitre’s security officer, Bill Chandler, who is skeptical that a secure site could be the source of a breach. Cliff also calls “Teejay” at the CIA, who is shocked by the Mitre lead but maintains that the CIA cannot involve itself in domestic affairs. Finally, the Air Force Office of Special Investigations (OSI) takes an interest, realizing that the path is leading toward high-level defense and intelligence targets in Virginia.

Thoughts

“It’s not in my bailiwick” is a phrase that is mentioned multiple times in the book. It manifests even today in many ways. Though the bureaucracy is probably less now than in the past, the tendency of ‘it is not my responsibility’ is there everywhere. Say a data breach occurs where a massive corporation loses your data (I’m reminded of Equifax, which was fined over $ 500 million), they might offer a year of credit monitoring and an apology. But who is truly responsible for the “digital pollution” created by that leaked data? Is it the user for trusting the service? Is it the company for failing to secure it? Is it the regulator for not enforcing stricter standards? If the answer is ‘all of the above’, then the actual answer is ‘none of the above’. “Shared Responsibility” has become a buzzword, but what about the knowledge asymmetry? Is everyone involved really knowledgeable about the responsibility they need to take?

Quick Recap (Thanks to NotebookLM)

(this section)